Friday, September 10, 2010

MULLAH RELEASES EID MUBARAK WISHES

Every time Mullah Omar issues a statement, the news reports have a familiar ring. The “reclusive Taliban chief,” or the “notoriously media-shy Taliban leader,” we are told, has issued “a rare” public statement.

The reports go on to add that Omar “has not been seen in public for years”, or at least since he went underground after the 2001 fall of the Taliban.

A number of men on the FBI’s most wanted terrorist list have not been seen in public for years. But unlike the publicity-savvy al Qaeda leaders, such as Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, Mullah Omar is believed to be quite a different kettle of fish. Taciturn, shy and not well versed with the ways of the world, the Taliban chief is not your average jihadist windbag.

Or so we’re told.

Over the past few years though, with clockwork regularity, the Taliban’s self-proclaimed Emir al-Momineen, or commander of the faithful, has been issuing statements to mark major Muslim festivals.

The latest one, marking Eid al-Fitr, the feast that marks the end of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, appears to be a pre-emptive “mission accomplished” proclamation.

The 3,000-word declaration in four languages, which was posted on jihadist websites and relayed by the US-based SITE Intelligence Group, claims that the US-led coalition forces, which are “hammering out new strategies, admit themselves that all their strategies are nothing but a complete failure”.

The Taliban leader goes on to declare that the “victory of our Islamic nation over the invading infidels is now imminent”.

In form and content, Omar’s Eid ul-Fitr 2010 message is not that different from his 2009 one.

Nearly a year ago, Omar maintained that the fight against foreign forces "is approaching the edge of victory".

Nearly a decade after their movement was ousted from power, the Taliban are viewed as a group of largely illiterate, madrassa-educated Pashtuns who emerged from the villages around Kandahar with an aversion to everything modern.

While the top Taliban leaders – known as the Quetta shura – are overwhelmingly madrassa graduates and their conception of governance and human rights is outdated, they are not at all averse to modern means of communication.

In recent years, the Taliban have created a “sophisticated communications apparatus that projects an increasingly confident movement,” according to a 2008 report by the Brussels-based International Crisis Group.

“There have been statements from the Taliban leadership commenting on the (Jan. 2010) London Afghanistan Conference, on a UN report on civilian casualties, statements are regularly released for Eid festivals and a lot of other occasions,” says Thomas Ruttig of the Kabul-based Afghanistan Analysts Network. “The Taliban’s media output is definitely increasing,”

The medium is the message: From mobile phones to DVDs

Besides the leadership messages on jihadist Web sites, the Taliban have effectively employed a range of media geared to a largely illiterate audience.

These include SMS texts and mobile phone ringtones featuring nationalist tunes, a potent medium in a country that had no cellular coverage in 2001 but today boasts about 9.5 million subscribers.

Audio cassettes providing morale-boosting martial songs are especially popular with truckers, although many truckers say they prominently display these cassettes to avoid security problems in Taliban-controlled areas.

DVDs feature a jihadist version of action movies with clips of attacks – in Afghanistan and Iraq – set to rousing music.

It wasn’t always this way. When they were in power in Afghanistan from the mid-1990s to 2001, the predominantly Pashtun group were notoriously inept at getting their message to the outside world.

Inside Afghanistan, the state-controlled Radio Voice of Sharia dominated the airwaves. On the international front, the movement’s archaic ministry of culture and information struggled to justify actions such as the March 2001 destruction of the Bamiyan Buddha statues to the international community.

The reasons for the new communicative face of the Taliban are diverse, according to Ruttig. “Technology has obviously advanced and can be used to their advantage,” he notes. “Then, there are a lot of young people in Afghanistan and Pakistan who are educated and well versed with technology.”

A cacophony of spokesmen with contradictory messages

The change has not come overnight, but has been gradually honed over the past few years.

“The Taliban have managed to reduce the different voices coming out of the movement over the past eight or nine years,” notes Ruttig. “In the first years after the fall of the Taliban, there were different spokespersons often giving different versions of the situation. But this ended quite a while ago.”

It was not uncommon for news outlets in Afghanistan to receive faxed Taliban statements refuting comments by other purported spokespersons. Later, the movement appeared to assign two spokesmen for two geographic zones. Qari Mohammed Yousuf, popularly referred to as Qari Yousuf, appeared to cover the south while a certain Zabihullah Mujahid spoke for the northern and central regions.

The two names are widely believed to be noms de guerres and many journalists suspect there are different people answering the same telephone numbers.

Since the Taliban are comprised of semi-autonomous insurgent groups functioning around the core Quetta shura, it’s not always possible to keep the disparate arms of the insurgency in check.

For a while, the reigning star of the Taliban media was the fiery Mullah Dadullah, who had a proclivity for displaying gruesome hostage beheading images before he was killed in a May 2007 clash with Afghan and international forces.

Taliban sources subsequently confirmed Dadullah’s killing and some experts believe that his gruesome style fell afoul of other Taliban commanders who provided the intelligence that led to the successful May 2007 attack.

Refining the propaganda

By its very nature, Taliban propaganda is bombastic, self-serving and quick to take credit for attacks and even military accidents in the insurgency-hit areas.

But in recent years, the Taliban have attempted to refine the propaganda.

Over the past two years, the movement has issued codes of conduct, mirroring the codes issued by top US commanders in Afghanistan.

The aim of the Taliban codes of conduct, according to Ruttig, is more propagandistic than realistic. “The codes call on fighters to avoid attacking civilians or executing people or attacking people for money,” notes Ruttig. “But in practice, that’s not always doable.”

Another consistent Taliban media move, over the past few years, has been to emphasize the nationalist nature of the movement.

Mullah Omar’s 2009 Eid ul-Fitr message, for instance, stated that “We assure all countries that the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, as a responsible force, will not extend its hand to cause jeopardy to others”.

It’s a message that starkly differs from the pan-Islamic al Qaeda-linked jihadist sites. But then, as previously noted, Mullah Omar is not your average jihadist windbag.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

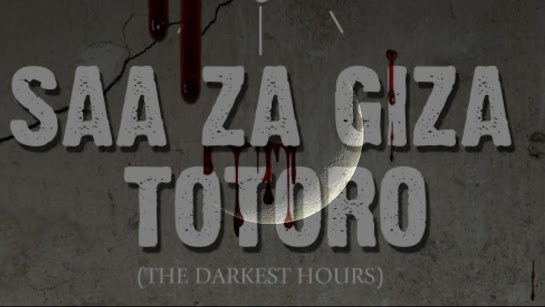

THE DARKEST HOURS (SAA ZA GIZA TOTORO)- 1

Mtunzi: Hashim Aziz (Hashpower) 0719401968 “Ngo! Ngo! Ngo! Fungua!” “Nanii?” “Fungua!” “Jitambulishe kwanza, wewe nani?” “Nimese...

-

Geneviv ni binti mdogo ambaye amezaliwa katika familia yenye maisha mazuri sana.Mungu amemjaalia kuwa na sura nzuri yenye mvuto.Bahati mbaya...

-

HASH POWER 7113//Acreditation: Global Publishers Wanausalama wakizima moto uliosababishwa na mataili yaliyochomwa na wachimba kokoto...

No comments:

Post a Comment